Sciatica: what it is and how to treat it

Sciatica’s debilitating, making every little task painful, never mind training for a triathlon. Here, physio Christos Kostas explains causes, symptoms, treatment and prevention

Some triathletes might be at more risk of sciatica than others and, for those athletes, it can put them out of sport for weeks at a time and be hard to work around. But what exactly is sciatica, what are the warning signs, how do you treat it and, better still, how do you prevent it in the first place?

What is sciatica?

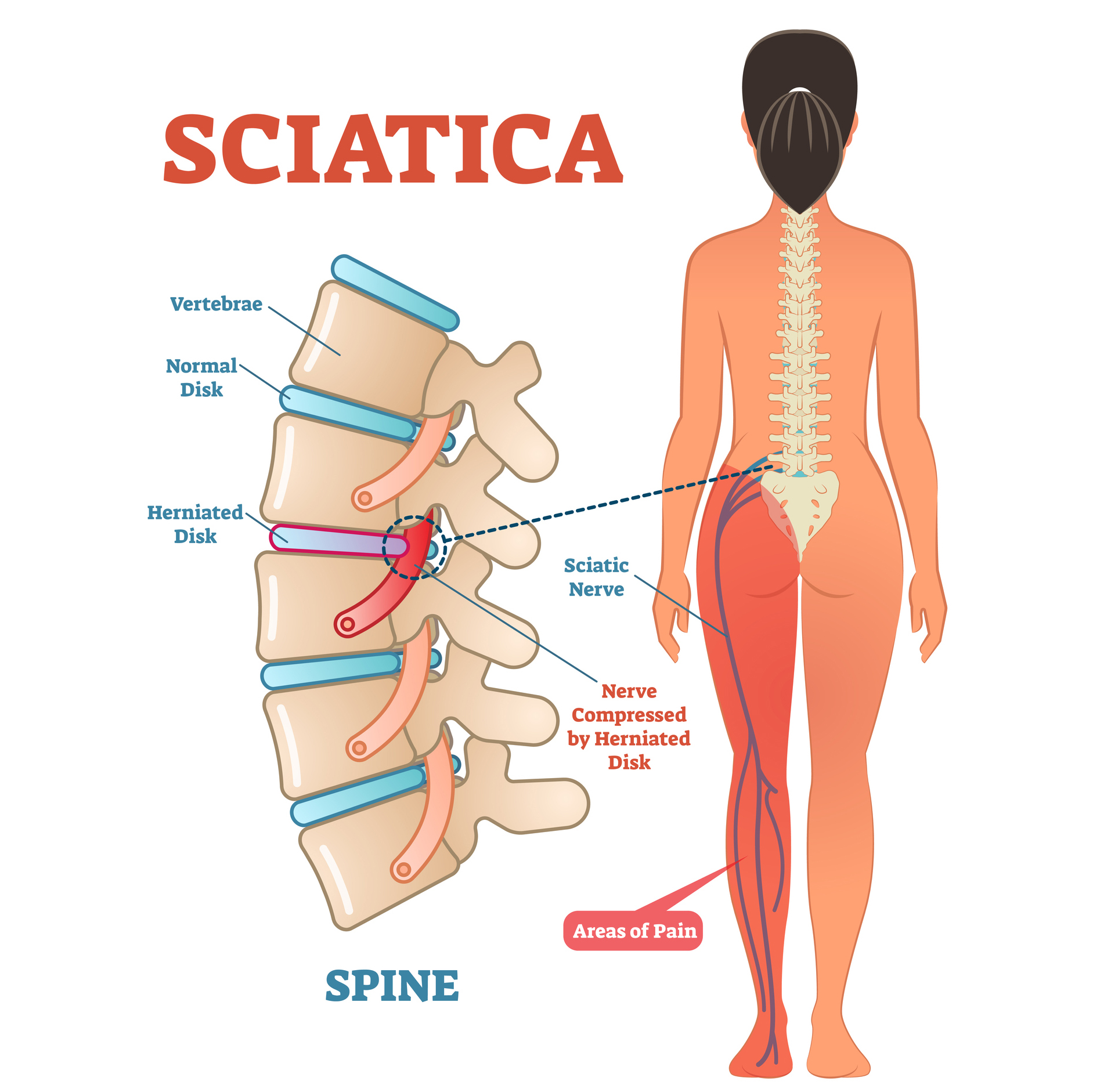

Sciatica is named after the origin of the pain it causes – the sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve in the body, starting in the lower spine, going deep in the buttock and down to the feet.

Sciatica generally flares up for four to six weeks, but in some individuals it might last longer. As the sport of triathlon has continued to grow, increasing numbers of triathletes have checked into neurosurgery clinics with complaints related to various spinal issues (1).

What causes sciatica?

Sciatica is generally caused by the nerve being trapped, whether it be by a herniated disc, bone spur on the spine or, most commonly, a tight muscle trapping the nerve. For triathletes, muscle compensation from past injuries (that haven’t fully recovered) is the most common cause of sciatica.

The condition is actually relatively common in athletes and the general population alike. One questionnaire directed at triathletes specifically found that lifetime incidence of lower-back pain was 67.8% with 23.7% of cases possibly starting with disc problems (1). Of the three sports incorporated in triathlon, cycling seems to have the major risk factor for lower-back pain in triathletes (2).

It’s important to note that most people over the age of 35 have a disc bulge and feel no symptoms. Indeed, even if you have sciatica and a disc bulge, it’s relatively rare that that is the cause of your sciatica. So don’t panic.

What are the symptoms of sciatica?

Common symptoms of sciatica include:

- Back pain

- Pain in the back of the leg

- Hip pain

- Burning or trickling sensation

- Shooting pains in the lower body

More often than not, the pain will fire through one side of the body if the legs or feet are affected, not both.

Sciatica might be diagnosed immediately if it follows a significant accident or injury. If it’s more of a slow onset that worsens over time, it might take a little longer to get a treatment plan in place. Initial assessment will involve questions and being asked to ease into a few different stretches or exercises to determine which results in the most pain.

Further tests can involve examining nerve impulses and imaging of the spine to look for abnormalities such as a slipped disc.

How can you treat sciatica?

Most people will reach straight for an over the counter painkiller such as Ibuprofen when pain and inflammation strike. This can certainly be a tool used in the short term to allow for sleep and day-to-day life to continue without being impeded too much, but we also need to look into longer-term solutions.

Hot and cold treatment can also be useful for short-term relief. An ice pack wrapped in a towel can be applied to the area for 20 minutes a day to relieve swelling and inflammation, especially after a competition or training session has caused sudden pain. After two or three days, you may find heat application is more beneficial. The two can be alternated to determine which is most effective.

If you have a prolapsed disc that doesn’t need urgent surgery, your best cause of action is to build the muscles of the lower back – strong things rarely break!

If it’s muscular, a good physiotherapist would identify the muscles in spasm and release them in two or three sessions. Only then would they prescribe a specific stretching programme (stretching can make acute sciatica worse), followed by strengthening exercises to further support the back. A strength programme with barbells – not bands or bodyweight – is the secret to preventing repeat injuries.

Stretches to improve posture and relieve some of the tension of the nerve can be helpful in treating sciatica. These might include cobra poses, prone arm and leg lifts, and upper pigeon poses. Core strengthening can also be useful. A qualified physiotherapist will be able to advise on the best stretches and exercises for you depending on the severity of your sciatica.

If lumbar disc herniation is the culprit, acupuncture has great success rates of 96.7% in a trial of 30 patients (3). Acupuncture is a treatment of traditional Chinese origin where fine needles are inserted into the body – in this scenario, into the sciatic nerve trunk – for therapeutic benefit. Treatment can be available through a GP or physiotherapist on NHS referral, or through private appointment.

In rare cases, sciatica cannot be repaired with these options. Surgery is the last resort for about 5-10% of people with sciatica. The two most common types of surgery are discectomy, which involves removing the part of the disc putting pressure on the nerve, or microdiscectomy, which uses a microscope to remove the disc through a small incision.

What is nerve flossing and how can it help sciatica?

An effective technique to alleviate the pain is ‘nerve flossing’, says Nick Beer, which repeatedly mobilises and releases the sciatic nerve through the lower leg’s soft tissues. E.g:

1. Lie on your back and pull the knee of the affected side towards your chest.

2. Place both hands on the back of the thigh and hold the knee in a fixed position.

3. Slowly begin to straighten the lower leg. Maintain dorsiflexion of the foot until you feel the stretch. Hold for no more than 1-2secs. You should feel the stretch through the back of the knee, hamstring, calf and possibly the foot.

4. Release and return to the start position.

5. Repeat x 30.

Please note, this is not a sustained stretch and should not be held for long if you’re experiencing pain. When the pain becomes manageable, try these two variations:

As above, but hold the knee in the fixed position. Flex and point your foot x 30.

Increase the difficulty by adding a large resistance band.

How can you prevent sciatica?

The two main risk factors for long-term spinal problems include sports-related injuries and overuse (1). For this reason, it can be beneficial to work on factors such as form and technique while running or on the bike to prevent unnecessary pressure on the spine and nerve. This is where a good strength programme focusing on your hips, glutes and lumbar erectors – the muscles that support your spine – will help. When we repeat the same action thousands of times our body fatigues, causing our technique and posture to fail. The stronger we are, the longer we can keep in an optimal position. This protects the back and spine and leads to faster times.

It’s also key to have a programme that allows adequate rest between training sessions. This might mean periodizing training so that volume and frequency change over the season.

The chance of developing sciatica can also be increased by being overweight. Assuming most reading this are healthy and active, this is more something to be mindful of for later life if you’re already experiencing some symptoms. Age and inflammation are also risk factors for sciatica. As you age, be sure to maintain mobility in your hips and ankles. Two good tests are your ability to sit comfortably cross-legged on the floor for five minutes and to perform bodyweight squat below parallel without your heels lifting off the floor.

As you age, be sure to maintain mobility and flexibility in your back. Also, be sure to combat inflammation with antioxidants from eight or more portions of fruits and vegetables. I’d also recommend the use of dietary supplements such as a daily dose of omega-3.

Like with any health issue, if you have any concerns at all, seek medical advice from a qualified medical practitioner, whether that’s a doctor or physiotherapist,

Christos Kostas is a physiotherapist with salecca.co.uk

References

(1) Villavicencio, A., Burneikienë, S., Hernández, T. and Thramann, J., 2006. Back and neck pain in triathletes. Neurosurgical Focus, 21(4), pp.1-7.

(2) Manninen, J. and Kallinen, M., 1996. Low back pain and other overuse injuries in a group of Japanese triathletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 30(2), pp.134-139.

(3) Qiu, L., Hu, X. L., Zhao, X. Y., Zheng, X., Zhang, J., Zhang, M., & He, L. (2016). Zhen ci yan jiu = Acupuncture research, 41(5), 447–450.

Images by Getty